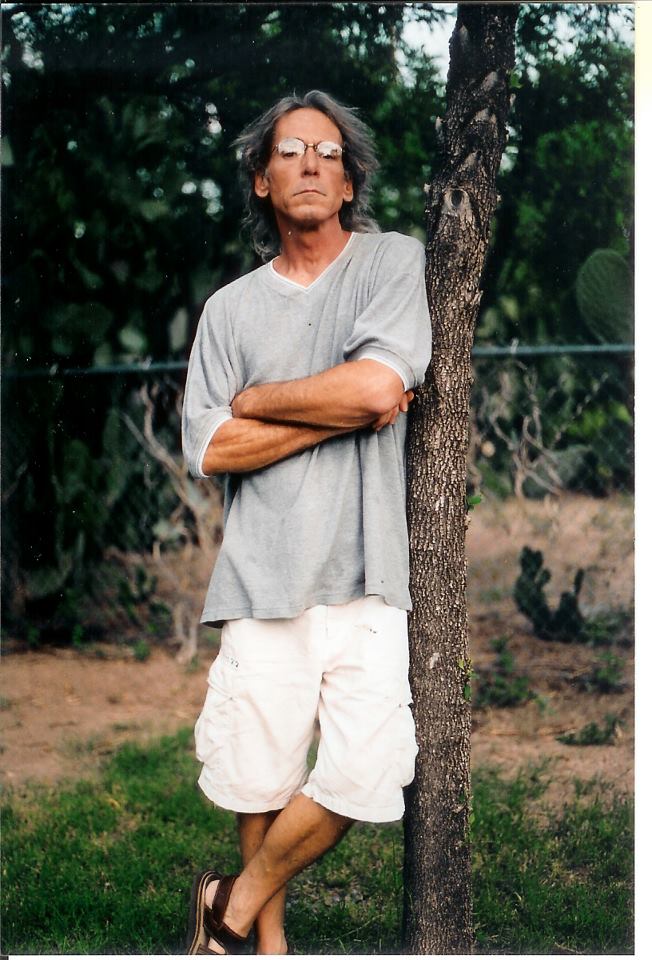

Studio Tablinum: Paul Scott Malone is a successful American artist, he lives in Huston -Arizona- and, after a brilliant career as writer and journalist, he has decided to dedicate himself totally to the thing that he most love: Picture.

I call him “Paul” because he asks me so and, as you can note, this is an important element which underlines that Paul isn’t only a great artist but also a great person.

I’d like to present him with this interview, I leave to you the pleasure of discovering him!

“How did you discover this passion?”

“How did you discover this passion?”

“I discovered this passion when I was a young boy. My mother, a painter of roses mainly, though she also painted landscapes and portraits, saw some hidden talent in me and took me to summer art classes when I very young at the studio of her best friend and my “god mother,” you might say. It was great fun to smear oil paint all over a canvas and go home covered in paint, and for several years in my youth I was convinced I wanted to paint pictures of anything for the rest of my life. So I started out painting flowers and a few landscapes because that is what I was being taught how to do. The change to abstract came many years later.”

“But you are also an established writer, right? How did you develop this your second passion? And what was the role of painting during this period?”

“As my life progressed, and especially during my college years as I read more and more of the great masters of literature, I discovered a love writing too. I let my passion for painting move to the background of my artistic life, still doing a little drawing and painting, but focusing my attention on fiction and poetry. I worked as a newspaper journalist for about five years to earn a living, but I was drawn to greater heights. So I returned to college as a graduate student and took an MFA degree in creative writing and contemporary literature from The University of Arizona in 1986. During those years I wrote and read constantly. I also edited a textbook on rhetoric while I was in graduate school. Several of the short stories I began during that time of joy and study eventually found their way into my first book but only after years of editing and re-writing as I was also making other stories and starting what would become my first novel. That first book called “In an Arid Land: Thirteen Stories of Texas” was published in 1995 and won Best book of Fiction from the Texas Institute of Letters in 1996. It also received a very favorable half-page review in The New York Times Book Review shortly after it was published. I went on to write two more books of fiction “Memorial Day and Other Stories” and my only novel to date “This House of Women” which was also honored with a very prestigious award from an organization of Western U.S. librarians called Women Writing the West. I was the first man to win this award.

But I could not keep oil painting from intruding on my writing life, and in the mid-90s it finally took over as my principal means of artistic expression –due to, also, for my mother’s death-.

I embraced oil painting as my primary way life in 1997, when I painted (oil, pastel, watercolor, pencil, charcoal, anything) more than 100 works in oil and pastel, not to mention hundreds of sketches and drawings. By then, there was no turning back. The more I painted the more the passion grew. I thought about it constantly, dreamed about it, and worked 12, 14, 16 hours a day. When I sold a few pieces, I was finally taken over completely. I love everything about the works themselves and the whole process of painting. I took a few drawing classes to help me improve in that area, but by then all I wanted to do was paint pictures. In 1998 and 1999 I made more than 200 paintings, some small, some quite large. This was a love that grew from a place in my heart that I was not even aware of in those days. I visited Europe several times to see the work of every old master I could find in Italy, France, Germany, Spain, the UK . Everyplace I could get to see more and more paintings.

For many years my work teetered between relativism and the abstract. Realism never really interested me for some reason, even though I made a few realistic drawings and paintings in those years (all destroyed now) just to prove to myself that I could master realism if I chose. I chose not. By 2004-05 I discovered that I had a real talent for oil painting, a talent I could never ignore. I dropped everything else and went completely abstract. The love, the passion, only grew. Now I could not imagine my life without painting! anything, everything. Even the smell of oil paint and all the other elements that go into a painting attracted me to my studio as a butterfly is attracted to a beautiful flower. I was a painter of abstract paintings! I could not go back now if I tried, whether or not others appreciated what i did. I painted for myself first and if someone else enjoyed it well, then, all the better. Now, art is all that matters to me in my working life. I hope to die in my studio.”

“So, let’s start with another question! First of all, you have said that you have visited Europe so,by which artists have you been more impressed?”

“I traveled to Europe several times eager to seek out whatever of the old masters I could and anything else that might show me the way. I enjoyed all the masters just fine but it wasn’t until I saw up close the work of the Impressionists, Van Gogh especially of course, that I started to see what I wanted to do with my own work. I was never a realist but Impressionism revealed a new way of seeing everything : flowers, faces, love, cruelty ; everything)and I realized that what lies before our eyes is seldom the truth in life. It may be a reality of some kind, if anything is real, but it is not the truth we find in our souls and hearts and minds, which are so often crowded with hundreds of visions and desires. I call upon anyone to show me one absolute reality (beyond earth wind and fire perhaps) and I know personally that truth comes in many more disguises. But then truth is not in our grasp. By searching we may catch glimpses; that is all.

And then there was Picasso. And Matisse. Lucien Freud. Jackson Pollack. Dozens of others. No one obscure whom I think has been overlooked, though there are plenty. Most art does not impress me in the slightest. But then there was Mark Rothko. When I was in college I spent hours sitting in the Rothko Chapel near the school gazing at his huge canvases with nothing painted on them but one color, a color that changed as the sun passed by the windows, but always returned where it began the next morning. I thought for many years that Rothko had exhausted the need for an artistic dialog; he had refined it to its barest element: color. He had shown us that to create deep thought, deep emotion, deep harmony required nothing more than color. Everything else was superfluous. And for a brief time I fell under his spell, though I never painted pictures with nothing on them but two shades of orange or purple. Still, he had shown me that the dialog of art -what does and does not constitute great art? – is so far, ranging as to be never ending, yet still quite simple. The difficulty lies in the question.”

“And have they influenced your paintings?”

“To avoid any taint of imitation, I virtually stopped going to museums or galleries, reading art books, seeking out other artists to meet, art parties. In fact, to this day, I could count on one hand the number of acquaintances I have whom you might call artists. I lived then, and still do, a very secluded -almost reclusive -and quiet life, and I would have it no other way. I attended graduate school in creative writing at The University of Arizona and grew to love the desert, the remoter parts of the US, which seem still so incomplete. I live about 60 miles north of the border with Mexico and there is very little here but sand and cactus and desert animals. In this place, and for years, I searched, trying out everything on canvas or on paper and it all usually ended up destroyed.”

“When did you find your method of painting?”

“In 2004, I found it quite by accident. The tool was an air gun, not an airbrush, but an air gun, the sort of thing one uses to inflate automobile tires and do other difficult jobs in factories or garages. I blew some paint around on a canvas I was entirely displeased with and -wham!- there it was. I have no idea where it all came from, but the more I tested it the more I saw. I saw images that sent me into spasms of thought, colors I had never dreamed were possible, emotions that made me weep.

Most everything I had done before was burned or hidden and I knew I had finally found my path in life. I scoured the Internet, pored over books, looked everywhere and could find no one else making paintings such as these. Some were similar, but still far from what I had discovered. With brushes and other implements I still paint, but mostly I rely on blowing paint around until I see something , whatever. Sometimes it takes one wash, sometimes twenty or thirty. Sometimes one day, sometimes four or five years. Almost always though I find the picture that had been hidden in all that paint, or something close.

So I abandon it and move on.”

“So you have embraced Abstractism, have not you Paul?”

“So, yes, I have fully embraced abstraction. I paint or draw an occasional nude or portrait but I seldom include the ears (I hate ears!) and the other body parts are often distorted and in one case the face is resting on a kind of oblique scaffolding -a touch of cubism in that one, I suppose-. And most people consider my work strange or bizarre or unworldly; or just poorly done, as if I don’t know my job. But there is something strange or bizarre or unworldly about all great and fine art. Look at Goya’s “The Third of May, 1808.” Look at Rubens’s “The Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus.” Look at Van Gogh’s “The Starry Night.” All of them: how threatening! To most people, I suppose, the unusual, the mysterious, IS threatening. But great artists have always, whether they knew it or not, delved into the human heart and soul to see what they might find, and, to reveal what they saw, portrayed sometimes the motion and sometimes the calm of what we consider reality. Thanks to them there is much wonderful art in the world.

Abstract artists do the same thing but in a more direct and, I believe, truthful way. The mind, to me, is just as vast and various as the physical universe is immense and marvelous. Whose mind is not in a state of constant disarray, constant change, even in sleep, always brimming with often-unknown ideas, music, anxieties, confusion, images, delight, mystery? Who knows what else lies within? We must go and search. Abstract art, lacking the formality of the past, is the best we’ve got just now to go looking into the illusive internal life for its sources and mechanisms, which the artist must then struggle to convey in a manner that can be shared with others. My work is not meant to startle; it’s what I see. It asks questions that cannot be answered yet, tries out answers that may make no apparent sense because there is nothing else, except the night sky perhaps, that can offer even a glimpse of the bizarre mystery of life, no matter what religion says. While we have learned a lot over the centuries about the workings of existence, we still haven’t the slightest notion of all the possibilities that lie out beyond the blue, the sun, the stars, much less what truly has evolved deep inside our minds and hearts and souls. Thus, the artistic dialog continues, leads us; and it must. History is a story of advancement into new, distant and even frightening realms, for good or ill. I think we should carry on with the story.”

“Do you think that people who see your canvas understand your message or they see only blots of colours?”

If I have been asked once I’ve been asked a thousand times virtually the same thing when someone is viewing one of my abstract paintings: “Is there supposed to be some kind of MEANING or MESSAGE in this?” My usual answer, because I don’t care to devote much of my one precious lifetime to such an absurd observation (it’s not a sincere question, it’s a bit of mean sarcasm in truth and because I find it usually ends the discussion) is to say simply that the picture means whatever you want it to mean. The message is whatever you want to see in, or hear from, the blots of color on the canvas. People usually shake or nod their heads and that resolves the topic.

Most would not understand my real answer, which is even more direct and very simple: Is there meaning or a message in anything but for stop signs and dark clouds? And why must art -fine art at least- express a meaning or a message anyway? Fine art does not need to draw tears from our eyes, anger us, instruct us, or even be beautiful.

Who am I to tell you what to think, in words or in paint, offer up meanings or messages for you to disagree with? These would be only my opinions and impressions of the natural world, or the often outrageous ways of humans, and I am not a prophet from heaven sent to show you the way, speak the truth, invent the wheel.

I am only an artist, a painter, as others are mechanics or CEOs, and this is what I paint because this is what my delightful imagination has revealed to my conscious mind, which in turn has shown me a path to take, to try out, whether or not I understand why or where I’m going. The destination will reveal itself when I get there.

“What do you mean with “often outrageous ways of humans”?

“Russia recently invaded Ukraine and, under threat of overwhelming force, took away Crimea from the people of Ukraine. Russia may or may not have been in the right or the wrong, but underlying it all is a big question: Will this act, this way of humans, lead to more war, more death, more destruction on the Earth? It was, to me, as a citizen of the world, an outrageous act committed by one nation, or collection of humans, against another nation, or collection of humans. Art doesn’t care, or shouldn’t care, whether Russia was right or wrong.

By the phrase “outrageous ways of humans” I mean only the things we do to others, or to ourselves, or that others do to us, which seem unusual or unnecessary or unethical or immoral, the sorts of things we read about in the newspapers and know about from history. Is it my place, as an artist -should it even be necessary- to make a painting, or write a story, let’s say, that would obviously condemn Russia for doing what it did? Must I, as an artist, condemn murder, rape, theft, cruelty, barbarity, greed, aggression, war? They condemn themselves.

Anyone with the gentle sensibilities to appreciate fine art would find a “message” superfluous on the part of the artist. Some may even find it insulting, as I do, since anyone who has the capacity to appreciate fine art probably already knows what he or she thinks about such things without my telling them. Blots of paint on canvas are much more interesting, and certainly more fun.”

“Now I would like to ask you this thing: You said that war, murder, rape, theft, cruelty, barbarity and greed condemn themselves, so you do not feel the necessity to condemn them openly. That’s right?

But I have seen, in your website, that there is a serious of pictures titled “Black” and I have supposed that maybe are connected with this discussion, some of them seems atomic explosions for me!

They are really impressive, why have you decided to call “Black” this serious of pictures? What is connected to them?”

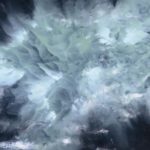

“I’m glad you see a meaning in the series, perhaps those lines and blobs and colors DO represent atomic explosions; I don’t know. It’s a perceptive observation, no matter what, and a great way for you to understand and classify for yourself what you are looking at. Your imagination is at work! And I’m glad you see a possible message in the title “Black,” for that is certainly the mood created in me, too, when I hear of, or read about, or see a picture of, an atomic explosion. We all know what that could mean: Does nuclear war loom on our horizon? A dark deed if ever there was one.

At the same time, when I’ve allowed myself to look for something concrete in those paintings, I’ve always seen things like caterpillars and scenes of stellar peace; the quiet sky. Oddly, I do have a series of about a dozen large paintings called “Eruptions” which I myself don’t understand beyond the concept of “eruption.” The paintings look as if they may represent eruptions. But even Coca-Cola can erupt. A soccer ball, if over-inflated, can erupt. In addition, I made another series of paintings that is just as explosive as “Black” but I titled it “White.” Why?

Let me tell you a brief story. When I first started selling my paintings about twenty years ago I always put titles on them. At that time my work was not as abstract as it is now, so the titles often came out something like this: “Flower Pot with Zinnias” or “Reclining Nude” or “Dream of the Grand Canyon.” When I made the break with realism -at least in oil painting – and aligned myself more and more with the abstract I realized the difficulty in applying a name to blobs of paint on canvas. What would be the title? “Blobs of Paint on a Canvas”? That wouldn’t get me very far. So I started calling most of my paintings only by their composition numbers (or serial numbers) as in “Composition 351” or “Composition A85.” It was like naming them “Untitled” only it made it easier for me to remember which painting was which.

But some friends and mentors complained. They said that I should give the viewer a hint, some way to label the painting, lead the viewer in some direction no matter how vague. Finally I consented. Again oddly, it just so happens that I was finishing up most of the paintings in the very series we’re discussing, so I looked at them closely, for several weeks, and I eventually realized that the only thing they had in common was the color black. Each one had at least a little black paint in it. So I titled the series “Black.”

And now the last question: “What are you painting now?”

“Right now I’m finishing up a series called “Red.” It’s called “Red” because its most prominent color is red, as I intended it to be. All five of the paintings are beautiful and full of mystery, the source of all emotion. When I get good photos of all five I’ll send them to you.

But I’m also -besides trying to earn my daily bread, which grows more difficult every day – doing some preliminary thinking and muddling about on a continuation of my series called “Canyon.” I have some canvases, already stretched, with some old paintings on them that I don’t care for; I disagree with the dialog they are offering; but they are all done in earth tones, which are my favorites to work with. I want to take what is already there and, with the knowledge and mastery I have gained over the years, I want to transform them so that the colors and the lines and all of that painterly stuff leaps off the canvas and grabs you by the nose and says: “Look! Look at what I am, for you have never seen me before and will never see anything like me again. Enjoy it while you can.”

I love to paint; I adore painting and painting of every kind.

Since I returned to Arizona almost two years ago -the desert, real desert in all its naked beauty – from Texas (which has only a little kind of ugly desert in its western regions) I have renewed my awe of arid places and what they tell us about our past and ourselves even today. Not so much the desert sand and the cactus themselves, but the general atmosphere which the desert offers a painter is rare on the Earth. It’s like a woman, ugly or beautiful, no matter, a model who has a lot of body to paint, curves and angles and strange moods hidden in her bones, soft places too, a body that reveals the tremendous depth of our real humanity. We’re animals and spirituals combined! As I said before, the place appears to be only half finished, or half naked, as if too much of its slip is showing (to use an old phrase) and perhaps a breast or two, or even a sweet round belly; all of that is in the desert pose as well. The shapes and the colors and what it all says about our Earth’s heritage is quite awe inspiring. In many ways, everything I do comes from the arid Southwestern United States. It is not only a gorgeous model but an excellent pallet, if you know what to do with her.”

“Thank you very much Paul, it has been a really interesting interview for me. I hope that Arizona, the desert and the reality of life continue to inspire you and let you express your inwardness; you have this quality and it is not something common.”

- P.S.M. – “White #6”

- P.S.M. – “City Heat #6”

- P.S.M.- “City Heat #4”

- P.S.M. – “Oblique Reflection #3”

- P.S.M. – “Black #8”

- P.S.M. – “Black #2”